October 27, 2014

Anarchists unite!

To really scorch the earth, as in a nonstop Sherman's March to the Sea, the means of destruction have to be led and organized.

In the conduct of his own personal life, Rokuta is more of a libertarian with a healthy disregard for centralized authority. Even though he chooses the emperor, he afterwards denigrates him with every other breath (the feelings are mutual, though they don't let it interfere with their work).

Libertarianism of late has become a synonym for anarchy. Even accepting that premise, anarchy as a political abstraction is not the same as chaos. Kant defines anarchy as "law and freedom without force," and Webster's (Random House) offers as one definition:

a theory that regards the absence of all direct or coercive government as a political ideal and that proposes the cooperative and voluntary association of individuals and groups as the principal mode of organized society.

In theory, of course. The typical rejoinder to the idealistic anarchist and strident libertarian is: "So do you want to live in a place like Somalia?"

It's one of the dumber strawman arguments out there. But as it turns out, somebody has answered that question for real. Peter Leeson at George Mason University analyzed the data and concluded that the average Somalian was, in fact, better off stateless.

State predation can actually reduce the welfare of the citizenry below its level under statelessness.

The data suggest that while the state of this development remains low, on nearly all of 18 key indicators that allow pre- and post-stateless welfare comparisons, Somalis are better off under anarchy than they were under government. Renewed vibrancy in critical sectors of Somalia's economy and public goods in the absence of a predatory state are responsible for this improvement.

The human proclivity to self-organize is so deeply rooted--it would have been a key trait advantaged by Darwinian selection--that it takes a real outbreak of entropy to eradicate it.

Sherman's March to the Sea lasted a little over a month, the Civil War four years. More prolonged conflicts such as China's Three Kingdoms period (220–280) and the Thirty Years' War in Europe (1618–1648) can indeed turn apocalyptic in the scale of destruction. Everybody looses.

Except China and Europe are still here. Civilization can take a drubbing and bounce back pretty quickly.

During its Warring States period (1467-1573), Japan's internal political order was similar to that of the Italian city-states. The tiny amount of arable land pretty much meant that the combatants had to live where they fought when the fighting was over. So "scorched earth" was pretty much out.

Armies march on their stomachs, and that requires a thriving agricultural economy plus a trading surplus, because guns and swords don't grow on trees. All the more reason to shepherd your resources, even when raining down fire.

NHK's historical dramas will usually toss in a few scenes depicting the warlord inspecting the fields, dealing with unhappy farmers, supervising the construction of levees, and auditing accounts. This was what warlords spent most of their time doing, not fighting.

Only a few scenes, grant you. Cinematic anarchy (The Road Warrior) makes for better fiction than reality. Push come to shove, I'd prefer a little too much government than too little. The problem is that a "little too much" has so easily turned into "way too damned much."

Even there, what concerns me the most isn't necessarily the size of government as the distribution of government. In other words, if you think Northern European countries represent the epitome of functioning democracies, first consider their size and population distribution.

Sweden, for example, has about the same population as North Carolina. Germany has twice the population of California (biggest in Western Europe) but is smaller in area than Montana. When distributing government services, population density matters too.

The "economy of scale" is the great temptation of modern-day governance. The problem is, building big things is easy. Managing them is hard. Far more people think they have the chops to run big organizations than they actually do. At least in the private sector, those people can be fired.

When it comes to governing, small is more than "beautiful." It's the only political philosophy that will reliably work over the long term.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, deep thoughts, history, japan, nhk, politics

October 23, 2014

Hanasaku Iroha

Ohana's mother runs off with her boyfriend (a step ahead of the debt collector) and sends Ohana to live with her grandmother, who owns an inn way out in the sticks. The grandmother is in no mood to play babysitter and promptly sets Ohana to work in the inn.

Ohana is the quintessential heroine of Japanese melodrama: can-do and relentless optimistic (to the point of driving her roommate bonkers). And yet Hanasaku Iroha manages to stay true to the core of its main characters, even at the cost of a happily-ever-after ending.

The grandmother had wanted Ohana's mother to take over the inn, but moving to the boonies is absolutely the last thing she has any interest in. The key dramatic arc in the series explores this irreconcilable conflict between the mother and grandmother.

So it's up to Ohana's uncle to manage the place. Except everybody knows--including himself--that he simply hasn't got the chops, even when joined by his MBA-grad girlfriend (incapable of uttering a sentence unadorned by incomprehensible American business jargon).

These nuts and bolts are treated with a light touch throughout, making Hanasaku Iroha an altogether pleasant comedy about running a small (failing) business in the country.

Along with the "how to" genre (how to run a hot springs inn), Hanasaku Iroha also belongs to what I'd call the "wabi-sabi" genre. As Wikipedia defines it:

Characteristics of the wabi-sabi aesthetic include asymmetry, asperity (roughness or irregularity), simplicity, economy, austerity, modesty, intimacy and appreciation of the ingenuous integrity of natural objects and processes.

A more idealistic western counterpart might be the "Hudson River School," that paints the countryside with a sepia-tinted palette. As urban and rural Japan have grown further apart, that distance hasn't lent itself to cool objectivity but to exaggerated romanticism.

Nevertheless, Hanasaku Iroha comes to a bittersweet conclusion more closely aligned with the realities of modern Japan: things that can't go on forever won't, no matter how much positive mental energy is poured into them. Though there is always room for a sequel.

Hanasaku Iroha is streaming on Crunchyroll and Tubi.

Labels: anime reviews, art, crunchyroll, personal favs

October 20, 2014

L.M. Montgomery's free-range kids

I'd seen the latter too, which was in no way encouraging. Sullivan's Anne of Avonlea (also known as Anne of Green Gables: The Sequel) is a good example of how to deviate from the source material while keeping true to its substance and spirit.

The Continuing Story is a good example of getting it all wrong. Sullivan manages to turn Anne, as Kate puts it, into a "bucolic female James Bond." Yes, it's supposed to be about Rilla, but the lead had to be Megan Follows. Like I said, it's a mess.

Rather, Joe points to Rainbow Valley as the standout in the post-Green Gables books. So I clicked over to Project Gutenberg and downloaded it. And he was right. Rainbow Valley is a real gem.

As Joe points out, Rainbow Valley is less about the staid Blythe kids than the wacky Merediths. They're the offspring of the eccentric and widowed minister. Following the death of his wife, the children mostly raise themselves (not a social worker in sight).

Things only get dicier when Mary Vance shows up, the orphan girl they take in like a lost dog.

Mary Vance is the alternate universe version of Anne. While Anne coped by filling up on literature, focusing her mental energy inwards and fueling her imagination, Mary Vance turns hers outwards, with the goal of controlling the chaotic world around her.

Not surprising, given an upbringing that makes Anne's pre-Green Gables life look comfortable by comparison. Nowadays, Mary Vance would be cast as the pitiful victim on a Law & Order episode, a serial killer's childhood flashback on Criminal Minds.

"My grandfather was a rich man. I'll bet he was richer than your grandfather. But pa drunk it all up and ma, she did her part. They used to beat me, too. Laws, I've been licked so much I kind of like it."

Or pumped full of Ritalin and handed over to Child Protective Services. But a century ago, a tough childhood gave a kid "character." Indeed, Mary Vance isn't looking for excuses. To be a "victim" is to not be in control, and that's that last thing she wants.

Mary tossed her head. She divined that the manse children were pitying her for her many stripes and she did not want pity. She wanted to be envied.

With her considerable wit focused so long on day-to-day survival, the attendant niceties long ago went by the wayside. And so unconstrained by a still nascent superego, her id leaks out all over the place. She definitely gets all the good lines.

"Mr. Wiley used to mention hell when he was alive. He was always telling folks to go there. I thought it was some place over in New Brunswick where he come from."

"I haven't got anything against God, Una. I'm willing to give Him a chance. But, honest, I think He's an awful lot like your father, absent-minded and never taking any notice of a body most of the time, but sometimes waking up all of a sudden and being awful good and kind and sensible."

"Give me Daniel [in the Lions' Den]. I'd rusher have it 'cause I'm partial to lions. Only I wish they'd et Daniel up. It would have been more exciting."

"If one has to pray to anybody it'd be better to pray to the devil than to God. God's good, anyhow so you say, so He won't do you any harm, but from all I can make out the devil needs to be pacified."

As Miss Cornelia puts it, "If you dug for a thousand years you couldn't get to the bottom of that child's mind."

But Mary Vance hardly has the story all to herself. In the second half of the book, the misadventures of the untethered Meredith kids take over the story, along with the emergence of a possible romantic companion for their father (a sweet note to end on).

Reading Rainbow Valley is like listening to a gossipy small-town newspaper read aloud, the chronicler now and then stepping back from the narrative to offer an aside or two about her subjects. But always with the best intentions--and honest empathy--in mind.

Although I shy away from the omniscient point of view, Montgomery's relaxed command of the narrative is such that the "head hopping" never bothers me, and even imbues the story with a touch of magical realism that places it apart from the real world.

Though with the Great War just over the horizon, the book briefly breaks the reverie at the very end with a haunting bit of foreshadowing.

This was certainly a great part of Montgomery's appeal in Japan. Hanako Muraoka completed her translation of Anne of Green Gables during WWII. The Japanese edition was published in 1952. "Reality" was one thing they didn't need any more of.

Though as far as reality goes, Rainbow Valley hews closer to my own childhood (considerably less than a century ago) than the nanny state reigning today. Back then, the only parental constraint imposed on us as we flew out the door was: "Be home by dinnertime."

Labels: anne, book reviews, free-range kids, kate, social studies

October 18, 2014

Poseidon of the East

Maps

Notes

Covers

Glossary

Downloads

Labels: 12 kingdoms, ebooks, fantasy, japanese, poseidon, translations

October 17, 2014

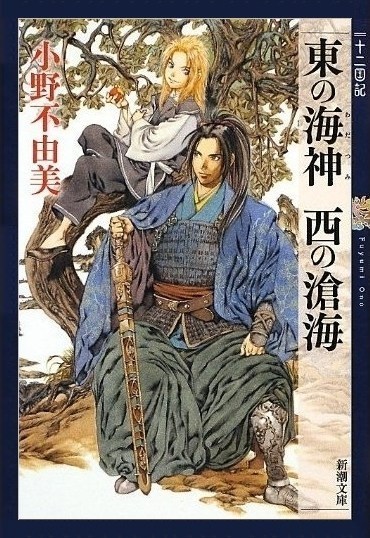

Poseidon of the East (covers)

2014 edition

Maps

Notes

Covers

Glossary

Downloads

Labels: 12 kingdoms, fantasy, japanese, poseidon, translations

October 16, 2014

Poseidon of the East (notes)

Maps

Notes

Covers

Glossary

Downloads

Labels: 12 kingdoms, fantasy, japanese, poseidon, translations

October 13, 2014

Side by Side

Reflecting trends on the still camera side, ARRI, Panavision, and Aaton no longer make film cameras. That film and camera production peaked only ten years ago illustrates the rapid adoption of digital since 2002, when George Lucas shot Star Wars: Episode II entirely on digital.

There's plenty--a glut--of used film equipment lying around. The more pressing question is how much longer Kodak can afford to keep making (and chemically processing) celluloid film.

Fujifilm quit the motion-picture film business in 2013. Kodak's film sales have fallen a staggering 96 percent since 2006. Like vinyl LPs, there will always been a niche market. Whether the economics of film can continue to justify blockbuster quantities is another question.

Right now, it seems that only guaranteed minimum orders from a handful of Hollywood heavy-hitters are keeping the Kodak film franchise alive.

Television's quick adoption of digital also contributed to the rapid decline of film. But we should also pause to thank the original 35mm prints of Star Trek and other TV "classics" for the brilliant, high-def versions available today.

Along with a brief history of the evolving digital film technologies, Keanu Reeves interviews directors and cinematographers with competing analog vs. digital loyalties. If nothing else, this documentary rekindled my admiration for George Lucas as a technological pioneer.

Digital projection is the last frontier. That frontier is closing fast. In its heyday, most of the motion picture film stock Kodak made was used for theater projection prints. That market sector has taken biggest hit as theaters switched to digital projection.

IMAX was a lone holdout for a while. The last 70mm IMAX theater in Los Angeles will have a 4K laser projection system by the end of 2015.

As with still film cameras, the question not "if" but "when." The most ardent film aficionado has to admit that the best film stock in the world is ultimately no better than the worn-out print running through the crappy projector with the dim bulb in the local mall theater.

And lastly, there is the unavoidable irony of watching a documentary about the motion picture business in which the "old timers" extol the aesthetic superiority of analog--using digital technology.

Labels: movie reviews, movies, star wars, technology, television

October 09, 2014

Poseidon of the East (40-41)

The nengou system (年号), called kokureki (国歴) in the novel, resets to year 1 upon the accession of a new emperor. In the past, an emperor could designate a new nengou whenever the fancy struck him, which Shouryuu seems fond of doing.

Taika (大化) and Hakuchi (白雉) are the earliest recorded nengou in Japanese history, marking the reign of Emperor Kotoku (645-654). Daigen (大元) is also the name of the Great Yuan Empire, founded by Kublai Khan after he conquered China in 1271.

Japanese of Shouryuu's time would have been quite familiar with Kublai Khan, thanks to his two failed invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281, ultimately foiled each time by the "Divine Wind" or Kamikaze.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, history, japan, japanese culture, nengou, poseidon

October 06, 2014

Let them eat Cheerios

At the ends of the earth was an ocean called the Kyokai, the "Sea of Nothingness."

Two realms sat at the borders of its eastern and western reaches. Although normally cut off from each other, with no communication or commerce passing between them, the same legend had arisen in each--of a land of dreams far across the horizon.

Only a chosen few could visit that blessed and fertile place, where riches gushed forth like fountains, whose people, free from pain and suffering, neither grew old nor died.

In Shadow of the Moon, Rakushun articulates the substance of the legends:

"It's said that the people of [Japan and China] live in houses made of gold and silver, studded with jewels. Their kingdoms are so wealthy that farmers live like kings. They gallop through the air and can run a thousand miles in a single day. Even babies have the power to defeat youma [monsters]."

Rakushun looked at Youko expectantly.

Youko shook her head with a rueful smile. What a strange conversation this was. If she ever returned to her old world, nobody would believe her. Fairy tales, they'd say. And here, her world was a fairy tale as well. She laughed to herself. She'd believed all along that this was the strange and mysterious world. But in the end, wasn't she and the place she came from all the more so?

Actually, Rakushun is onto something here.

Farmers in any developed nation today live longer and better than medieval kings. Vaccinations, antibiotics, and water chlorination can defeat invisible demons once responsible for a 30 percent childhood mortality rate. You can fly from Seattle to Tokyo in 10 hours.

In 1866, Tokugawa Iemochi, the second-to-last shogun, died of heart failure at the age of twenty, presumably due to beriberi. Considering that the third-to-last shogun went bonkers and died at the age of 34, two centuries of inbreeding was probably taking its toll too.

In any case, beriberi is a disease brought on by vitamin B1 deficiency. Thanks to enriched flour, beriberi is almost nonexistent in developed countries today. A bowl of Cheerios a couple of times a month could have prevented it (and many other diseases).

The shogun was done in by a diet of polished white rice the poor couldn't afford. In the time travel series Jin, Dr. Jin Minakata invents yam donuts to save an old lady who won't eat anything but white rice because, you know, she's not poor anymore!

Labels: 12 kingdoms, history, japan, medicine

October 02, 2014

Poseidon of the East (39)

For the next 650 years (aside from the brief resurgence of the Southern Imperial Court), emperors reigned but did not rule (they really didn't rule after 1868 either). The head of state was the shogun ("generalissimo"), though he was more the hereditary prime minister in a one-party state.

With the Osaka Campaigns (which destroyed the Toyotomi clan, the one remaining threat to Tokugawa rule) and the Shimabara Rebellion over by 1638, there wasn't any generalling left to do, which left the shogunate woefully unprepared when Admiral Perry showed up in 1853.

Labels: 12 kingdoms, history, japan, poseidon